Southern California Edison said it is confident in its plans to store tons of highly radioactive waste at San Onofre indefinitely. But reports that the company knew about potential problems with faulty steam generators and installed the system anyway has undermined Edison’s credibility.

The site

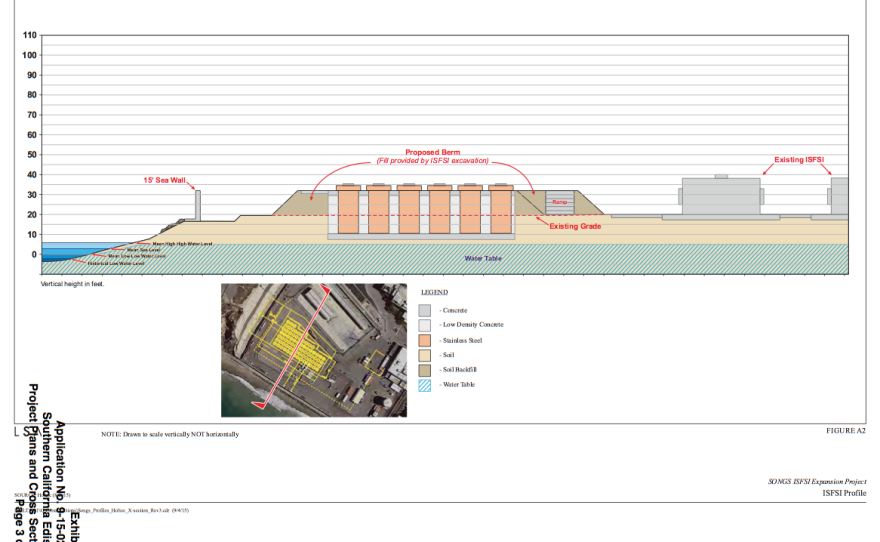

The site for storing the nuclear waste is sunk into the cliffs, right next to the Pacific Ocean, a little north of the familiar nuclear containment domes. Waves break below the seawall just 100 feet away, and beyond it surfers skim the water.

Edison, like all other nuclear plant operators, expected Congress to pick a permanent nuclear waste storage site by now. But in 2011, after more than two decades of research, Congress stopped funding a site at Yucca Mountain, 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

Tom Palmisano, Edison’s vice president for decommissioning, pointed to a concrete pad below him. This is where 75 stainless-steel canisters, packed with spent nuclear fuel assemblies, will be buried vertically in a concrete monolith, he said.

“You’re looking at the existing dry fuel storage installation, which is in stainless steel canisters stored horizontally in an above ground concrete module,” Palmisano said. “That’s where the new system will be installed. It will be set back approximately 100 feet from the seawall. That seawall, I believe, is 27 feet. That is designed for the maximum tsunami that would occur."

In places the seawall looks closer to 15 feet above the high tide mark. But Edison estimates that even if it were to be overwhelmed, that would not threaten the integrity of the canisters of spent fuel.

Seismic threats

The company has contracted with Scripps Institution of Oceanography to research seismic threats to the site.

Researcher Neal Driscoll plans to release findings in the next few months, but he said his research found no evidence of one of the two previously identified threats, namely the Oceanside Blind Thrust. The other fault, the Newport-Inglewood-Rose Canyon fault could generate activity. Driscoll said the San Diego Trough, which sits 30 miles offshore, acts as a natural baffle to reduce tsunamis caused by large quakes.

Edison’s plan is to partially bury concrete monoliths containing the stainless steel canisters with an earth berm. The nearly 20-foot tall canisters cannot be completely buried underground because they would be too close to the ground water table, he said.

This development stunned Ray Lutz, founder of Citizens Oversight Project, a watchdog group.

“If you had to choose a place to put this — that was the worst place you could think of, right here on the coast, within a hundred feet of the ocean and inches from the water level, that’s the worst place you could think of,” Lutz said. “And guess what the industry has chosen? That spot.”

Lutz said a spot in the California desert would be better. He’s identified a location near an isolated place called Fishel, which is not far from Ward Valley, a spot that was considered as a site for low-level nuclear waste. After years of study the site was rejected because it threatened the habitat of the endangered desert tortoise.

Edison does not own that land and it would take 10 to 20 years to develop and license an off-site facility, Palmisano said.

RELATED: California Commission Sued Over San Onofre Vote

After installing faulty steam generators, Edison’s track record of decision-making does not inspire confidence, Lutz said.

“If they fail on this plant, just keeping it operating, what makes you think that they’re going to make good decisions on this million year problem that we have here,” Lutz asked.

Lutz’ group is challenging a recent decision by the California Coastal Commission to issue Edison a 20-year permit to expand its nuclear waste on-site storage. The commission voted unanimously to approve the permit, agreeing that on-site storage is the only feasible option.

Commissioner Mary Shallenberger addressed the risks.

“A radioactive leak onto one of our beaches would definitely have an impact on coastal access,” Shallenberger said.

Inspection techniques

At an Oct. 6 Coastal Commission meeting, Shallenberger asked regulators why there is no way to inspect the canisters for leaks.

“Why is it that we are not asking for that information prior to issuing this permit?" she asked.

Mark Lombard, director of Spent Fuel Management at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, admitted at the meeting there is no way to inspect the canisters yet. He said they are working on new technology using tiny robots.

“It’s a not a now thing," Lombard said. “Because even we’re not comfortable with the technology that exists today, but it’s very soon in the future that these technologies will exist to detect cracks and also to detect how deep those cracks are.”

However, the contractor designing the canisters for San Onofre, Kris Singh, president of Holtec International — an energy industry supplier — said at a recent Community Engagement Panel meeting that finding and repairing a crack in a canister would be difficult.

“If that canister were to develop a leak — let’s be realistic — you have to find it, the crack, where it might be and then find the means to repair it, in the face of millions of curies of radioactivity coming out of the canisters," Singh said.

"My personal position is that a canister that develops a microscopic crack — and all it takes is a microscopic crack to get release — to precisely locate it is a tall order. So as a pragmatic technical solution, I don’t advocate repairing the canister,” he said.

Singh said he advocated for isolating a cracked canister in another “confinement.”

That leads to questions of how such a container could be moved off site, since the NRC has not licensed transportation for cracked canisters.

Storage canisters

Donna Gilmore, a retired San Clemente resident with a website devoted to safety at San Onofre, has asked the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to require Edison to use thicker canisters, like those used in Europe.

“They lied about the steam generators,” Gilmore said about Edison. “They have no credibility. That’s the kind of planning they do: ‘Nothing's going to go wrong. Nothing’s going to go wrong with the steam generators.’ Look how that worked out. Same people, same promises, you’d be a fool to trust them on this.“

Gilmore calls the promises of inspection techniques “vaporware.”

“We shouldn’t be buying vaporware,” she said. “Vaporware is something that doesn’t exist - ‘OK, buy these thin canisters, yes they might crack, we’ll probably eventually be able to find the cracks.’ Of course when they do, they won’t be able to do anything about it.”

But Palmisano remains confident.

“We all expected Yucca Mountain to have been opened by now and the Department of Energy to be systematically removing canisters from the site," he said. "That clearly did not happen, which leads to the need to renew the licenses and to put in place the inspection technology for the future.”

“I’m confident in the current status of the canisters that are loaded," he said. “I’m confident in the new system and we will have the inspection system in place.

Industry optimism

David Lochbaum of the Union of Concerned Scientists, said he advised Edison that burying the radioactive fuel in canisters would be better than leaving it in spent fuel pools. Edison plans to move more than 2,600 fuel arrays out of the pools by 2019. Lochbaum said while confidence is the nuclear industry norm, their track record doesn’t always warrant it.

“If nothing else, the nuclear industry is optimistic,” he said. “They tend to believe that things will be optimum. They don’t really plan for the worst. For example, the problems that led to San Onofre being closed - the steam generator tubes, when the plant was built and purchased, were thought to last forever. That didn’t happen, but the expectations were that things wouldn’t go bad.”

Efforts to find a permanent storage site failed after more than two decades of work at the federal level.

Palmisano remains confident new initiatives to find interim storage sites in Texas or New Mexico will succeed.

“What I’m confident about is that over the next 10 to 20 years these facilities are very likely going to be licensed and built,” he said. “And provide us the option we need.”

The storage canisters are warrantied for 25 years, though the concrete bunker they will be buried in is only warrantied for 10 years. While the warranties are part of the legal contract, Edison, as the licensee, remains accountable, Palmisano said.

The lack of a permanent storage site is a game changer for the industry, which is now faced with designing a waste management plan it had not anticipated. The nuclear fuel may remain on site for longer than the next few decades, stretching Edison’s confidence to untested limits.