Thursday marks the fifth anniversary of a violent confrontation between a Mexican national and U.S. Customs and Border Protection that was caught on camera, spurring policy changes within the agency.

On May 28, 2010, Mexican national Anastasio Hernandez Rojas suffered a fatal heart attack after he was repeatedly shot with a Taser at the San Ysidro Port of Entry. The San Diego County medical examiner ruled his death a homicide, but no charges have ever been filed.

Hernandez's family filed a wrongful death suit. Five years after his death, they're still waiting to go to court. His widow, Maria Puga, said she is determined to keep fighting.

“I’m not going to stay in my house, sitting down. I’m not going to stay there all depressed the way I was at the beginning,” she said. “I didn’t want to confront any of it.”

Hernandez was deported after living in San Diego for about two decades. He was trying to cross the border illegally to reunite with his wife and five children in the place he considered home, when border agents stopped him.

In the cellphone videos recorded by witnesses, at least a dozen agents are seen beating Hernandez, and repeatedly shooting him with a Taser as he lies face down, handcuffed, crying in pain and screaming for help in Spanish. One agent is seen removing Hernandez's pants.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection released a statement after Hernandez’s death, saying the use of force was deemed necessary for the safety of its officers.

The San Diego County Medical Examiner's Office found several broken ribs, loosened teeth and internal bleeding. The office concluded the death was a homicide and noted that Hernandez had methamphetamine in his blood.

Progress of Litigation

A federal grand jury investigation opened in 2012 is still pending. Some of the potential criminal charges, not including homicide, have a five-year statute of limitations. That means they expire five years after the incident if no indictments are made.

The Hernandez family's civil lawsuit names the U.S. government and the individual agents as defendants. The case has been repeatedly blocked from going to trial by defendant motions.

“They’ve done everything they can to drag their feet to avoid going to court,” said Eugene Iredale, one of the family's attorneys. He said the government offered the family a $1 million settlement last year. They rejected it.

The U.S. government had asked that the case be dismissed, claiming its agents were protected from civil liability under a doctrine known as qualified immunity. That doctrine says government officials can’t be sued for conduct that did not “clearly” violate constitutional rights. The judge denied that motion, and the defendants appealed. Now the family is waiting to see if the court grants their motion to certify the appeal as “frivolous.”

“Nothing has been done,” Puga said. “So much time has passed and nothing has been done. So you ask yourself, where is justice? Where is it?”

In response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed by freelance reporter Marty Graham, the U.S. Department of Justice said it had paid close to $1.37 million as of Sept. 30, 2014, to seven law firms that are providing counsel for the 12 Border Patrol employees involved in the Hernandez case.

More Migrant Deaths

Hernandez is one of 39 immigrants who died in incidents with U.S. border agents over the past five years, according to the Southern Border Communities Coalition.

Day Of Action

The Southern Border Communities Coalition is staging a Day Of Action in San Diego and other border communities at 5 p.m. Thursday, May 28. The San Diego event will begin at Sixth Avenue and Laurel Street in Balboa Park.

Shawn Moran, vice president of the National Border Patrol Council, said officers involved in migrant deaths were defending themselves.

“This number of people have been killed because they have assaulted Border Patrol agents,” he said.

He described the Border Patrol as “a model of restraint," saying, "Border Patrol agents use lethal force seven times less than the average law enforcement officer nationwide."

He added that immigrants in handcuffs still present a possible danger to the lives of Border Patrol agents. He said anyone who is actively resisting an agent poses a threat.

“Border Patrol agents go out there wanting to do their job,” he said. “They don’t go out there wanting to send someone to the morgue. That’s just not the way it works. Any death is tragic, but this individual had a choice in the matter, and he chose to fight border patrol agents.”

Moran said he would be shocked if the agents involved in the incident were indicted.

The U.S. Department of Justice did not respond to requests for comment for this story, and U.S. Customs and Border Protection declined to comment.

A Witness Remembers

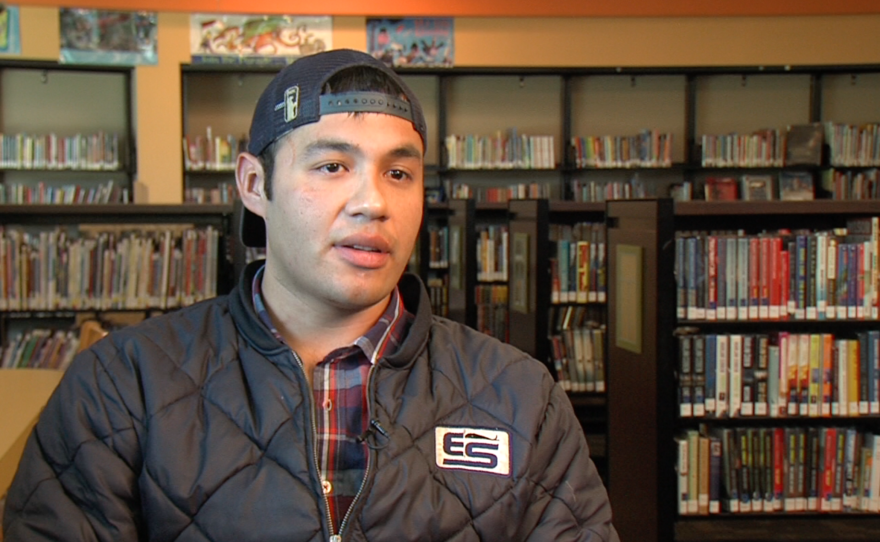

Humberto Navarrete is the witness behind one of the videos of the incident that went viral. He said he never saw Hernandez resisting. He said that’s why he pulled his cellphone out to record what was happening.

“In my eyes, it was an assassination,” he said.

Not much is visible in Navarrete’s video. But Hernandez’s screams for help and cries of pain are audible. In the video, Navarrete approaches an officer on the scene to protest the actions, telling the officer it was an "excessive use of force."

Navarrete said he has seen a therapist to cope with the trauma of what he witnessed. He said he sometimes looks back on the incident and wishes he had done more: taken down names or protested more decidedly.

Several other people had gathered to record and protest what they were seeing. But Navarrete was one of only two people who spoke up after the incident and shared his video.

“I know there are more people who were there that night,” he said. “I know there were lots of people. They shouldn’t be afraid anymore, of talking. ... We all have the right to know what happened that night.”

Promises of Reform

Christian Ramirez, human rights director at Alliance San Diego, said he thinks the Hernandez case represents a turning point in the way U.S. Customs and Border Protection treats migrants.

Last year, the agency agreed to tighten restrictions on use of deadly force after an internal review. The new policies improve training for agents in the use of less-lethal weapons and prohibits agents from putting themselves in situations where deadly use of force might prove necessary.

“There will be an after and a before history of the Border Patrol with this incident,” Ramirez said. “Because in the past, when border agents would kill Mexican-Americans or Mexican immigrants, nobody would cover these issues. It was just the way things were.”

Significant progress has already occurred. Customs and Border Protection is conducting a feasibility study on body-worn cameras. Immigrant rights activists are meeting quarterly with the agency's commissioner, R. Gil Kerlikowske, who has promised more reforms.

President Barack Obama did not include Customs and Border Protection in his $263 million budget proposal for implementing body-worn cameras among law enforcement nationwide for fiscal 2016, but Ramirez said he is optimistic about fiscal 2017.

“Now we are luckily in a position where we can dialogue with CBP. But how do we tell folks like Maria to be patient?,” Ramirez said.

Learning To Live Without Hernandez

“The hard part was when time started to pass,” Puga said. “(The children) were still waiting for their father. I said, your father is not going to return. He’s in the sky.”

Puga said her now-16-year-old son dropped out of school and has had to take anti-depressants because of his father’s death. Her 9-year-old twins often bring up what they perceive as the injustice of his killing. They were 4 when their father died.

“I tell them, I know it wasn’t OK, but … I can’t be poisoning them. I don’t want them to grow up with hate,” Puga said.

She said she tries to convince her children that they have to accept what happened and move forward with their lives. But she thinks part of the reason it has been so difficult for them is the delay in the legal process.

“The day justice arrives will be a relief. Emotionally. Because we’re never going to forget (Hernandez),” she said. “We haven’t forgotten him. We’ve just learned to live without him.”

Puga said Hernandez was an industrious construction worker and a doting father. He would return home from work covered in dust to cook dinner for the family and play with the children.

“I always said he took better care of the kids than I did,” Puga said.

Puga worked late at a tortilla factory, so Hernandez helped her with the household chores, keeping everything clean and organized. He built the children a playground with wagons, swings and an outdoor cinema.

Now, that space lies abandoned. Puga works full-time cleaning hotel rooms to support her children. She said she has found the support of the community and immigrants-rights activists invaluable in coping with her husband’s death.

Hernandez’s brother, Bernardo, is less optimistic. He said increased awareness about violence against migrants at the border isn’t worth much, considering the fact that 38 others have died since his brother.

“They still haven’t solved (my brother’s) case even though there’s videos and witnesses,” he said. “So much time has passed and there’s no solution."

He said a guilty verdict against the men involved in his brother’s death would provide him with “a little bit of relief.”

On a recent Tuesday, Puga took a poster of her dead husband to the San Ysidro border crossing, a few yards from the spot where he was beaten and shot with a Taser.

She said Hernandez visits her in dreams.

“I’ve always told Anastasio, I’m not going to rest until I get justice for you,” she said. “I’ve promised him and I’ve told him, if there’s no justice, there’s no peace. We need justice to have peace.”

She recalled the fear she felt whenever she was near the border back when her husband was alive. She was afraid of Border Patrol agents because she herself was not a legal resident. But Hernandez always reassured her. He told her Border Patrol agents were good people, just trying to do their jobs.

“I always remember those words of his,” she said. “He had so much respect for them. And they killed him.”

This report is part of KPBS's Fronteras Project, a regional news collaborative that produces reports on the changing culture and demographics of the American West and Southwest. Fronteras reporting is made possible by a grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.