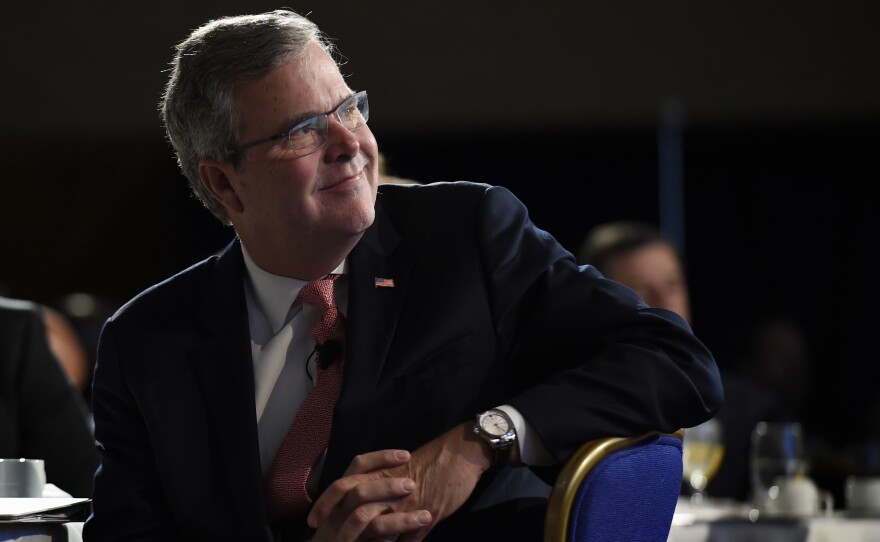

Prospective Republican presidential candidate Jeb Bush is moving to get his share via a new political committee. The way he did it could blaze a new trail for candidates seeking out million-dollar donors.

Bush's action comes just before the fifth anniversary, next Wednesday, of Citizens United, the 2010 Supreme Court ruling that restructured the campaign finance landscape. In the five years since, there's been an explosion of political money.

The organization around Bush, a former Florida governor, has created a superPAC, a species of political committee that wasn't possible before Citizens United. It can take contributions of any amount.

Confusingly, the Bush organization also set up another political action committee at the same time, an old-fashioned PAC operating with contribution limits. The PACs have the same name, Right To Rise, similar logos and the same lawyer.

Bush announced one of them – the old-fashioned one – in a smartphone video last week. Walking along a sidewalk in Manhattan, he told the camera, "Everybody, today we're setting up the Right To Rise PAC, which is a PAC to support candidates that believe in conservative principles to allow all Americans to rise up. If you're interested, go to righttorisepac.org."

But for wealthy donors who are deeply interested in Jeb Bush's political future, Right to Rise SuperPAC seems the better option. At the superPAC, donors can give hundreds of thousands of dollars, even millions of dollars. Bush can even solicit the big contributions himself — something he couldn't do as a declared candidate.

It's a new twist in post-Citizens United politics.

The heart of Citizens United is the notion that superPACs, and other outside groups, are completely independent of candidates. That underpins the Court's conclusion that unregulated money from big donors wouldn't be corrupting to lawmakers.

Federal law says federal candidates and officeholders can't coordinate with superPACs. But until Bush becomes a candidate, that restriction doesn't apply.

"So long as you do not take steps to actively and publicly campaign, then a superPAC is permissible," said campaign finance lawyer Craig Engle, who represented candidate Jon Huntsman in the 2012 Republican contest. "If you have a superPAC and there isn't a candidate, there's no worry of coordination because there aren't two entities that could be coordinating."

The Bush organization didn't respond to requests for comment.

SuperPACs were mandatory accessories for presidential candidates in 2012, often running devastating attack ads that the candidate's campaign preferred to avoid. Some of the superPACs were funded mainly by one wealthy donor – among them, Winning Our Future, supporting Republican Newt Gingrich and underwritten by casino magnate Sheldon Adelson and his wife; and Red, White and Blue Fund, backed by investor Foster Freiss to promote Republican Rick Santorum.

Now, as Bush is demonstrating, there's nothing to stop not-yet candidates from having superPACs too – Mitt Romney, Chris Christie, Hillary Clinton, anyone who isn't an announced candidate or federal officeholder.

"What Citizens United and related cases from the Roberts court have given us is a system that is pretty close to no holds barred," said Daniel Tokaji, a law professor at Moritz College of Law in Ohio, and co-author of The New Soft Money, a book examining the outside spending in politics.

He notes that many of the Watergate-era regulatory standards are still in effect. "But they're increasingly ineffective at stopping people from spending massive amounts of money to influence campaigns," he said. "So we're not quite to a completely deregulated system, but we are pretty darn close to that now."

This year, a well-financed pre-candidacy could be especially important. The 2016 primary season starts later than normal, with the Iowa caucuses in early February. Tokaji says White House hopefuls might follow Bush's lead, and "you could have what is in effect a wealth primary before the primaries and caucuses even begin."

It would be just another product of campaign finance law after Citizens United.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.