In 1993, Maria del Estrada witnessed a nightmarish scene from her home’s second-floor window in Colonia Chula Vista, a low-income neighborhood in a Tijuana canyon called Pedrera.

She saw women drowning in violent brown water currents in the street in front of her house. Some held onto newborns. Cars, ovens, refrigerators and other debris floated beside Estrada’s drowning neighbors.

An upstream settling tank, meant to retain mud and trash in water flows, had become clogged and then erupted. This created a towering wave that gushed through Estrada’s neighborhood.

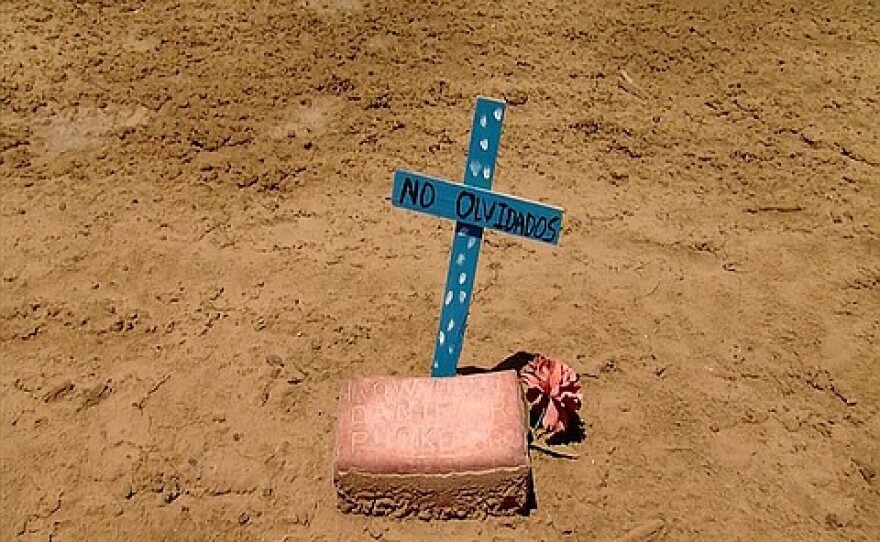

“It knocked down houses, and here there were 39 people dead,” said the 75 year old. “We heard them crying out for help, but who could help them?”

Cañon de la Pedrera is one of roughly 30 canyons in Tijuana prone to lethal flooding when it rains because steep hills move water into makeshift neighborhoods like Colonia Chula Vista, where houses are sometimes built with cheap materials such as corrugated tin, wooden planks and foundations of car tires. Loose dirt from the unpaved road in front of Estrada’s house slides into the nearest settling tank during rainfall.

Memories of the 1993 floods, which left thousands of people homeless, have moved Tijuana officials to make early preparations for El Niño, expected to bring heavy rains this month. Tijuana’s civil protection agency has been cleaning water infrastructure since August.

When KPBS visited Estrada, a tractor lifted mud and trash out of the settling tank nearest to her home, just footsteps away. She said she was grateful for the clean-up, but that she’s still nervous.

“They said it’s going to be stronger than the (rains) in ‘93,” Estrada said. “Imagine how we’re going to end up. I was young before, and I could run. Now I can’t.”

The rains in 1993 were not tied to El Niño weather patterns, but they left Estrada’s whole lower floor filled with mud.

“There were mountains of soil,” she said, gesturing around her living room. “Only soil was left in here.”

Estrada said heavy rains have forced her to rebuild her house three times.

The garbage problem

After 1993, the city expanded its water infrastructure from four settling tanks concentrated in Cañon de la Pedrera to 27 settling tanks across Tijuana, connected by 19 miles of canals. As of last week, the city had cleaned 26 of the 27 settling tanks.

Some are concerned these early preventative measures may have been in vain. “We clean the tanks, and when we turn around, people throw their trash again,” said Alejandro Cancino, head of Tijuana’s water infrastructure maintenance program.

One tank cleaned a month ago was already filling with mattresses, cardboard boxes, car tires, children’s toys, soda bottles and scavenging pigeons.

“It’s the lack of culture among people who take advantage of the rains to throw their trash into the water flow,” Cancino said.

Fifty-year-old Francisco Flores, who lives a block away from Estrada, said he had established a committee of neighbors to try to monitor littering, the main reason the settling tanks overflow.

“Some people lack conscience and they throw lots of stuff into the tank,” he said.

Just three months ago, the tank in front of Flores’s home overflowed during heavy rains, and the roads began to flood. He started packing his truck with his most valuable belongings, planning to escape, but then it stopped raining and the water level went down.

“We’re very worried,” he said.

Cross-border flooding

The water that passes through these canyons flows directly into the U.S., bringing with it everything it picks up along the way: dogs, car tires, garbage, even people.

“In some cases, they’re in the sewage lines, people get trapped because of heavy rains and debris coming in from Tijuana,” said Payam Tanaomi, public affairs officer for U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

That’s when Border Patrol agents come to the rescue.

“The priority for us is preventing people from entering the country illegally,” Tanaomi said. “But most of the time, because of the area we work in, we do turn into first-responders.”

The agency has a search, trauma and rescue unit with certified emergency medical technicians who can respond to calls when people are drowning or otherwise hurt.

Usually, metal grates are in place along the border to allow water to flow between the U.S. and Mexico while keeping out heavy debris, people and drugs. But during heavy rains, Border Patrol is forced to open the grates.

“We have to open them to actually keep the integrity of the grates,” Tanaomi said. “The fast-flowing water can reach real high speeds and the debris coming through can bend them or break the grates.”

Tanoami said smugglers sometimes take advantage of this to try to get people across when it rains. When the El Niño rains hit, Border Patrol agents will be stationed by the grates at the ready.

In Imperial Beach, which tends to flood, the garbage brought across the border blocks horse trails and leads to beach closures. Much of the trash comes from Los Laureles Canyon, directly across the border, where the neighborhoods are unincorporated and lack trash collection services. Anything loosened on this canyon gets dumped directly onto the Tijuana River Valley in the U.S., only five feet above sea level.

If need be during El Niño, Border Patrol agents will help evacuate these low-lying areas.

A new website for emergencies

Tijuana’s civil protection agency has been conditioning buildings throughout the city to serve as shelters during El Niño. Officials will deliver supplies such as blankets and food when the need arises.

To help residents find these, the city government launched a website called Catastro, from the word catastrophe. It includes navigable maps for finding Tijuana shelters, police stations, hospitals, settling tanks and more.

Catastro shows the details of each facility, such as the number of beds at a shelter or the number of officers at a police station.

During El Niño, Catastro will also feature real-time information on floods, mudslides and more.

“You can access it through a smartphone or a tablet or your computer,” said Cesar Arce Moreno, Catastro director.

Youths receiving emergency training

In the meantime, Tijuana’s civil protection agency is ramping up emergency preparedness training for schools, businesses and more. About 10,200 people have received training so far this year.

On a recent Wednesday, fourth-grade students at the elementary school Vasco de Quiroga in Las Torres, one of Tijuana’s most flood-prone neighborhoods, learned about El Niño.

“It’s going to rain more than usual,” agency instructor Isis Rivera told the classroom of children. “Yes? Or no?”

“Yes,” the children responded in unison.

After the session, the children shared some of what they learned with KPBS.

“El Niño is when it rains a lot," said nine-year-old Sherlyn de Jesus Pascal Garcia.

"It creates a lot of wind and can knock down houses," said nine-year-old Tranquilino Gonalez Lopez.

“At home you should have an emergency backpack, and inside of that backpack there should be food and other survival items," said eight-year-old Valentina Arellano Muñez.