When Maya Sapiurka started her biomedical Ph.D. program at UC San Diego, she assumed she’d follow the traditional route when she finished.

"I think most people go into grad school thinking they’re going to go into academia, going to be a professor, going to run their own lab," Sapiurka said.

Sapiurka will be defending her thesis next summer. Now that she's nearing graduation, she sees things differently.

"I’m really hoping to get into policy work, serving some kind of role communicating science to legislators, being a go-between between the government and the public and communicating science to non-scientists," she said.

Science PhDs' First Jobs in 2013

Academia: 29 percent

Government: 9 percent

Industry: 55 percent

Nonprofit: 4 percent

Other: 3 percent

Source: National Science Foundation

Sapiurka's shift away from pursuing professorships is part of a national trend. More science and engineering Ph.D. students are now getting jobs in the private industry, not academia, according to the National Science Foundation. In 2013, 29 percent of science and engineering doctoral recipients found jobs in academia, while 55 percent went on to jobs in the private sector. In 1993, 36 percent found academia jobs, and 45 percent went into the private sector.

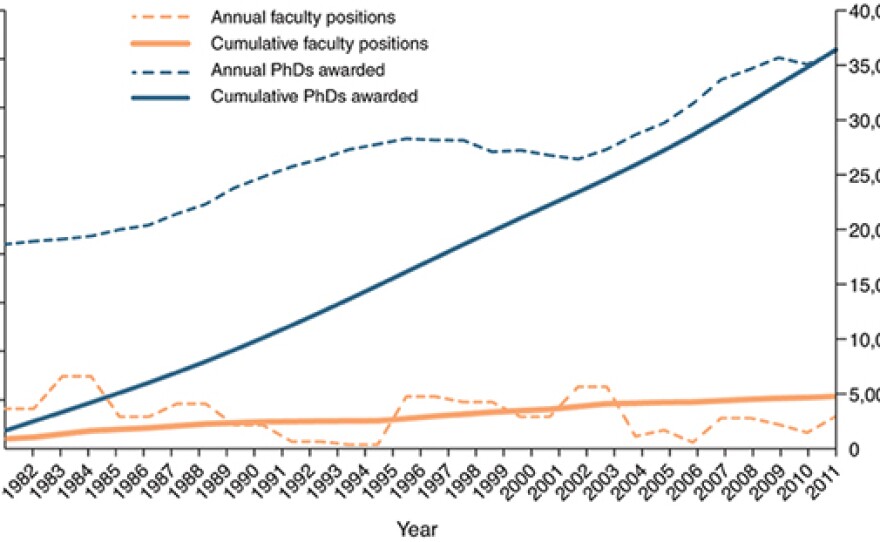

Part of the reason is that academic jobs are harder to find.

In the last 30 years, the number of people earning a science doctorate has skyrocketed, while the number of science faculty positions has barely increased. There are now more than seven times as many science Ph.D. graduates as science professors, according to the National Science Foundation.

It says less than 20 percent of science and engineering students are able to land jobs as professors within five years of earning their degrees.

But before you start feeling bad for those people with Dr. in front of their names, know that private companies want to hire them. So says Mary Walshok, associate vice chancellor of public programs and dean of UCSD Extension.

"There’s a demand increasingly for people with higher and higher level skills, more knowledge, more sophistication," she said.

Ph.D. students have those skills, but may not know how to fit in corporate culture, she said.

"You go through a Ph.D. program and you start thinking, 'I’m really an expert, I’m really a specialist,'" she said. "Yes, if you’re going to be in a classroom, yes, if you’re going to be doing research for scholarly journals."

But not if you’re working to develop a drug for market or make a presentation to investors. Walshok said Ph.D. students aren’t always taught how to manage a team, work on a tight timeline, or communicate with non-scientists.

So this year, UCSD started a program called Gradvantage to help graduate students fit in with the private industry.

Jonathan Monk is earning his chemical engineering Ph.D. at UCSD and helped come up with the idea for Gradvantage while serving as president of the Graduate Student Association last year. He said program organizers talked to local companies such as Qualcomm and Illumina to find out what skills students are lacking.

"It was really enlightening to me because they said, 'Look, we love graduate students, their technical skills are unsurpassed, they’re great, but they often lack humility, they always think they’re right,'" he said.

Gradvantage will include an intensive four-day workshop on communication skills and how to work well in a team.

"A lot of graduate students have a very linear relationship with their advisor and research, it’s kind of just them and the advisor working on a project, they might not have experience working with a big team of people on something that has to get done in the next week," Monk said.

The program will also provide job search tips and host career nights with professionals. Chris White, who earned a Ph.D. in chemistry from UCSD and then started the speciality brewers’ yeast company White Labs, will speak Wednesday at 5 p.m.

But not all Ph.D. students are ready to give up academia dreams. Cosmo Buffalo, who will finish his Ph.D. in biochemistry at UCSD this fall, said he's always strived for "the idea of the academic lifestyle and maybe the romantic side of it, this intellectual pursuit that comes with that."

Buffalo said he knows academia jobs are extremely competitive, but still hopes to become a professor. But first he’ll look for work as a postdoc, a temporary research job meant to prepare new graduates for faculty positions.

"The goal is to only do one, sometimes you can do two and still eventually be able to get a faculty position," he said. "It’s implied though that if you can’t do it after one then usually you have to start looking for other job prospects."

If that happens, he’d join the vast majority of graduate students who trade ivory towers for office buildings.