Cuauhtemoc Martinez tried to kill himself six months after he was deported from the U.S., where he had lived as long as he could remember. He threw himself in front of a speeding car in Ensenada. He woke up in the hospital with gashes and bruises all over his body. He said he still sometimes wishes he had died.

“I wake up with nightmares, sweats and everything,” he said.

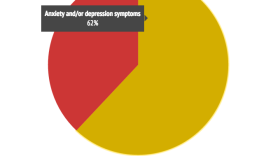

Martinez, 32, is among a rising number of Mexican deportees suffering from clinical depression, anxiety and other mental health problems. Few are receiving treatment. The largest wave of deportations in U.S. history – more than two million since 2008 – has been putting a strain on mental health resources in Tijuana, which receives at least 40 percent of the country’s deportees.

In some cases, psychological problems are pre-existing. But mental health experts say more often the diseases start in Mexico. The stress of being separated from families, jobs and homes in the U.S. turns into a full-blown mental health problem when combined with the hostile environment often encountered south of the border.

Martinez had worked as a supervisor at a Utah food-packaging plant, but he couldn’t get a job in Mexico after he was deported. He had no papers, and there seemed to be no record of his birth in the State of Mexico.

He was forced to work informal construction jobs. The arduous manual labor gave him asthma attacks and left him feeling exhausted. He said local police robbed him of all his money the day before he tried to kill himself.

RELATED: Tijuana Mandates Drug Treatment For Hundreds Of Homeless

“I was scared. I’m still scared. Sometimes I wake up scared,” he said.

When he was recovering from his injuries at a Tijuana migrant shelter called Desayunador Salesiano, Martinez started seeing volunteer psychologist Maria Rosa Ponciano for therapy. He was walking with a cane.

Ponciano helped him obtain his birth certificate. It was then that he learned his real first name: Cuauhtemoc, the name of the last Aztec ruler to fight the Spanish Conquistadores. In the U.S., he went by Luis. He thought that was his real name. That’s why it was so hard to find his official documents.

He hates the name Cuauhtemoc, but Ponciano insists on calling him that, hoping it will encourage him to develop a new sense of identity. She says few deportees are patriotic.

“They tell me, ‘I don’t want to be Mexican anymore!’” Ponciano said. “Because here they treat them worse than they did in the U.S.”

Ponciano said the sense of rejection from both Mexico and the U.S. sometimes makes her patients feel they have no identity at all. Sometimes, she said, this makes them suicidal.

“They feel they’re people without a right to live,” she said. “That’s how I hear them. 'I’m worthless, I can’t go over there, I can’t be here, what am I here for? I want to die.'”

A volunteer psychologist saves one deportee

When Martinez was first deported, he occasionally slept in El Bordo, a homeless encampment along the Tijuana river canal that has since been evacuated. He didn’t have a job yet, and had nowhere else to go.

Last month, in the latest response to the Tijuana mental health crisis, the local mayor sent the hundreds of people who were living in El Bordo to drug rehabilitation centers for mandatory addiction treatment.

Martinez was no longer living there when that happened. When he met Ponciano last December, she told him he could stay in a once-abandoned building her family owns in Playas de Tijuana, in exchange for cleaning it up.

He said he has never used illegal drugs, and that the sight of people using heroin and methamphetamine around him when he was staying in El Bordo compounded his feelings of fear.

Even now that he has a job and a place to stay, he sometimes feels overwhelmed with depression because of how much he misses the U.S.

“Sometimes I go over to the third floor and I see the ocean, I see the cars, how they’re living a great life,” he said. “And me? I’m miserable. I’m miserable in Mexico. I look down from the building and say, I can just end my life right now.”

He said antidepressants make him feel better, but they’re expensive, and he often runs out of them. He said he only feels okay when he’s keeping busy.

“I don’t think about the U.S. much when I’m working,” he said.

Ponciano said she often prescribes occupational therapy to the deportees she treats.

“So that they’ll feel useful,” she said. “So they know they’re not garbage from the U.S. Because that’s how they feel.”

Migrant shelters improvise solutions

On a recent evening at the shelter, more than a dozen deportees sat at a long table putting the finishing touches on homemade puppets they were making: gluing eyes on sponges shaped like heads, inserting clothespins for mouths that open and close, and making them speak both English and Spanish.

Rev. Oscar Torres, the director of Desayunador Salesiano, said an increase in deportees with mental health problems and the lack of formal infrastructure to treat them forced the shelter to improvise new ways to help.

The shelter has started several workshops, including contemplative dance, painting, sewing and the puppetry class to keep visitors’ minds occupied.

“If we want to attend the deportation problem at a human level, we have to attend them at emotional and psychological levels,” Torres said.

Another migrant shelter, Casa del Migrante, has hired a full-time psychologist to deal with the perceived increase in mental health problems among visitors.

One psychiatric hospital

The only psychiatric hospital in Tijuana where penniless deportees might be able to get thorough mental health treatment is called Hospital de Salud Mental, a lime-green building with curving stairways near the border.

But to access those services, they need to have Mexican health insurance, el seguro popular, which many deportees don’t have. They don’t have the documents needed to apply.

The director of hospitalizations at the Hospital de Salud Mental, Hector Paredes, said he has seen an increase in deportees suffering from chronic depression, anxiety, panic attacks and psychosis.

“When a person is exposed to intense stress, like a deportation, it can cause changes in state of mind, in thinking, in perception – and it has a fundamental biological component,” he said.

He said the stress of a deportation is more likely to cause chemical brain changes if individuals do not receive adequate treatment right away. He said all deportees should be evaluated for possible mental health problems.

The National Migrations Institute sometimes brings severely disturbed deportees to the hospital, but hospital experts are currently training migration officials to detect more subtle problems, such as depression and anxiety.

“It’s important to follow up with this population,” he said.

The self-medication problem

Carlos Correa, a psychologist at Tijuana’s CETYS University who worked with deportees in El Bordo, said many deportees turned to drugs to self-medicate because they saw no other options.

He said some developed addictions because underlying depression and other mental health problems went untreated.

“What starts as a process of grief turns into a chronic condition when there is no medicine or service available,” he said.

He said the deportation in and of itself can be a traumatic experience. Many of his patients report being mistreated by U.S. immigration authorities. Correa believes they're partly to blame for Tijuana's mental health crisis.

“We can avoid damaging the minds of these deportees by adding just a little bit of humanity to the process,” he said.

One deportee recovers

Carlos Guzman Garcia, 34, was deported from San Diego last year, after living north of the border for more than two decades.

He moved into El Bordo because it was the only place he felt safe. He said that he was afraid to wander around the streets because every time he did, the Tijuana police would stop him.

“The police right here, if you don’t have an ID with you, they take you to jail,” he said.

He said he was the routine target of police because of a large tattoo on his neck that displays the name of his daughter.

He said it was the pain of being separated from her, as well as the difficulty of life south of the border, that caused him to turn to heroin and methamphetamine.

“I was so depressed I was using drugs,” he said.

But his life changed when he met volunteer psychologist Ponciano. She gave him therapy and encouraged him to find a job.

Guzman said Ponciano helped him regain his self-confidence.

“When you see a person who helps you believe in yourself, and tells you that you can do anything, and that she’s going to help you … you change,” he said.

He has since stopped using drugs.

“We’re not garbage here. We’re just another human being. We really want to make it. We just need help, that’s all.”