TOM FUDGE: It is the season for signing bills, California Governor Brown has turned several bills into law this week. One of them changes the legal definition of consent for sexual assault cases that occur on college campuses. Universities have a process for investigating alleged rape, that can lead to the expulsion of a perpetrator. It is now not a question of whether the victim said no, it is a matter of whether the attacker asked if she wanted sex, and whether she said yes. On campus, we have gone from no means no, to yes means yes. If you did not get a yes, you can be found to have committed sexual assault. Joining me to talk about this new and controversial development are Jessica Pride and Joe Cohn. Thank you for joining us. Jessica, what was wrong with no means no a standard in these cases? JESSICA PRIDE: What was wrong is that the majority of the people perpetrating these assaults were not taking responsibility for their actions, they were not being prosecuted by the schools in the sense that there was no action taken. There were women going around campus feeling that they had wronged. There was no justice, they were not safe, and now you had in the issue that became big enough that this bill came about. What is the difference? What does it do? It puts the burden from where it used to be the victim having to prove that they said no, and here is the issue. The majority of women were intoxicated, and 80% of the women who are raped on campus are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. We're not going to tell college students not to think anymore. You cannot consent when you are intoxicated, some women cannot say no, I did not say no, because I was either drunk, or passed out under the influence of a date rape drug. So, what would happen, these girls would tell the school I have been raped, and the school would say no, I didn't, and it would say no case. And they would drop it. With the new legislation and the new law, instead they will say to the perpetrator of the alleged accused, did you ask her? Did you get a yes, verbal or nonverbal, did you get a yes? TOM FUDGE: Let me read you part of the law. Affirmative consent must be ongoing during the sexual activity and can be revoked at any time. Reading just that part, I wonder, does this mean that a person has to ask not one, but many questions? Now may I touch your breasts, now may I take off your clothes, is that the way that it has to go? JESSICA PRIDE: No, I think that is a little silly, and I think people are trying to portray it as such, to make it seem like such an extreme measure. It's saying do you consent to this? It can be verbal or nonverbal. If someone is participating, they are of sound mind and want to, ask the first time. The important thing is that a victim, woman or a man can take back consent at any point. Just because someone consented to kissing or part of the sexual act, it does not give that person carte blanche for anything they want that evening. TOM FUDGE: Right, but this law seems to say that the person cannot say no, it is on the other person to keep saying can we go ahead, can we continue, right? JOE COHN: Can I jump in on that? TOM FUDGE: Let me put this question to Jessica, and then we'll get you involved, Joe. JESSICA PRIDE: My interpretation of what is required is to make sure that both participants are willing. You do not necessarily have to say are you okay with this, you can say are you still going to be part of this, sure. We need to make it sexy and cool to say yes. That is the biggest thing that the message is trying to be sent. Students need to learn what incentives, and make sure everybody is having a good time and wants to be there. TOM FUDGE: Joe, let's get you involved. What do you think about all? Some people think it is necessary, what do you think? JOE COHN: I think the law is paved with good intentions, but a tremendous setback in reality for fundamental fairness. Also, in some ways, it will unintentionally endanger communities as well. I will get to that in a moment. I would like to touch on something that Mrs. Pride was a moment ago, that it was silly to require continuous ongoing consent, I think it plain reading of the text of the bill makes it clear that is required. If you touch someone in a way that they did not want to be touched, even if you start immediately after they tell you no, you have already committed sexual assault by not getting permission the first place. I have very little faith that Is administered as we make the distinctions that Mrs. Pride is trying to make. I've seen them but this in every direction of the course of years of looking at this problem. I think fundamentally the problem is that things are misstated here. Incapacitated people in California were already not required to say no. The law in California is clear that incapacitated people cannot give consent. This is a legislative fix that did not address actual problems. There were problems, and there's truth to the fact that there are student victims who did not always get the respect they needed from law enforcement or campuses, but this approach to the problem is misguided and family troubling. TOM FUDGE: I think I heard Jessica say that this shifts the burden to the perpetrator, not the victim. I think she believes that is good thing, what do you think of that? JOE COHN: I think it is fundamentally unfair, and almost impossible as a standard to meet. Therein lies the problem. I think it is true, again, when dealing with incapacitated people, that they are relieved of certain burdens that would ordinarily be there, because it is presumed they could not do it. The same with someone who freezes up during an attack. If it was reasonable to not resist or say no, if someone has a knife to your neck or is strangling you, we can come up with other examples, you are relieved of the burden already under the law before the bill was put in place. If you are accused of sexual assault now on campus, how do you go about proving innocence? The assumption is that all accusations must be true, and frankly, there is a healthy mix of true and false accusations. Regardless of the percentage, we need a system that is fundamentally fair on every single case. TOM FUDGE: Jessica, you have heard José a lot of things, what would you like to say in response? JESSICA PRIDE: In United States, 3% of men are victims of sexual assault. Right now, one in five women are sexually assaulted by the time they complete school. That is a horrific amount of assault on college campuses. You raised an issue if an attacker is strangling them. Rape, 80% of the time is done by someone the victim knows. It is someone at the party, or a friend of theirs. I want to say something as well, all rape is violent, and it is not necessarily involve being punched in the face, or pinned down. It actually involves someone freezing up, not realizing something is happening, and laying there, and unfortunately being raped. The biggest thing about this, is that the investigations are the problem. There were not people qualified, that had the proper training to investigate these. Second, these investigations were not done at all. If they asked the victim did you say no, that is where the buck stops. Instead, now, they will conduct an investigation, and if schools want funding, from the state of California, they will have to make sure they train first responders and provide resources to women, on campus or in the community. TOM FUDGE: Let me ask you something that I think your comments are leading to. And that is whether or not the university should be investigating these crimes. Is that a good idea? JESSICA PRIDE: It's a tossup some universities are equipped more than others. It depends on who is on staff. Usually the guide is the totality of the circumstances. Once they do an investigation, they are supposed to look at everything. Look at the witness statement, and make a determination. To keep it in perspective, we have to remember that the ultimate harm is that the person is expelled from school. This is not play over into the criminal justice system. It is not mean that more people are going to get convicted by a judge. That is not what we are talking about. TOM FUDGE: Isn't that something? At least to get someone expelled. JESSICA PRIDE: For most victims that is amazing justice. To walk around every day to see your attacker every day, that is horrifying and traumatizing every single day. TOM FUDGE: Joe, what do you think the fact that universities are doing these investigations which may result in expulsion? JOE COHN: There is no doubt that campuses have a responsibility to not turn it over to law enforcement and just wash their hands of the problem. That is established under title mine, and probably also the correct and ethical thing. The question we should be asking, what role should they be playing? I am not convinced, and the more I look at this I get less and less convinced that they should be trying to figure out who is innocent or guilty, or who is responsible or not. Trying to figure out who committed a date rape and who did not is out of their expertise, and trying to ask and English Department professor, and the anthropology department, and Dean of the physics department whether a date rape occurred without the benefit of forensic evidence or lawyers participating actively on both sides, without the benefit of discovery, without the benefit of rules of evidence that sort out whether something is admissible, hearsay or relevant, without the training and years of expertise that Miss Pride was mentioning, without the witnesses, the list can go on and on, I can take up the whole show talking about what they do not have at their disposal. And then, asking them to reliably figure out who did or did not commit these crimes is unfair to all parties involved. That is why we see so many injustices in both directions. We see women who do not get the help that they need and men who get in some instances, getting railroaded even though they are innocent. Let me make one more point. TOM FUDGE: Very quickly. JOE COHN: We heard that one in five women are victims of sexual assault in college, I will not contest that. But it is certainly in dispute, and there is very good reason why. We can all look at that very carefully. TOM FUDGE: Thank you Joe. Jessica, with just a minute to go, how will we know whether or not this new affirmative consent law is a success? JESSICA PRIDE: I think a benchmark would be that women feel safer on campus. That is the duty of every school, to make sure that women feel safe, couple, and have resources and are being supported. The other thing would be to see more women speaking up about being assaulted and bring you more like to this issue. Actually, in regular society, we have 50% of women who report. In college campuses, we have 12% of women reporting. If that increased, that would be amazing and to see more perpetrators being held accountable, and justice being done for victims, that would be a wonderful result.

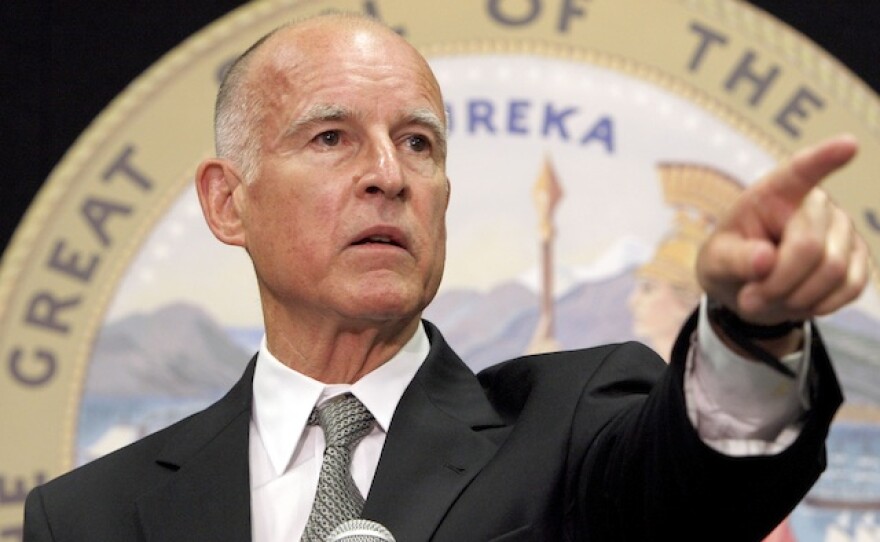

Gov. Jerry Brown announced Sunday that he has signed a bill that makes California the first in the nation to define when "yes means yes" and adopt requirements for colleges to follow when investigating sexual assault reports.

State lawmakers last month approved SB967 by Sen. Kevin de Leon, D-Los Angeles, as states and universities across the U.S. are under pressure to change how they handle rape allegations. Campus sexual assault victims and women's advocacy groups delivered petitions to Brown's office on Sept. 16 urging him to sign the bill.

De Leon has said the legislation will begin a paradigm shift in how college campuses in California prevent and investigate sexual assaults. Rather than using the refrain "no means no," the definition of consent under the bill requires "an affirmative, conscious and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity."

"Every student deserves a learning environment that is safe and healthy," De Leon said in a statement Sunday night. "The State of California will not allow schools to sweep rape cases under the rug. We've shifted the conversation regarding sexual assault to one of prevention, justice, and healing."

The legislation says silence or lack of resistance does not constitute consent. Under the bill, someone who is drunk, drugged, unconscious or asleep cannot grant consent.

Lawmakers say consent can be nonverbal, and universities with similar policies have outlined examples as a nod of the head or moving in closer to the person.

Advocates for victims of sexual assault supported the change as one that will provide consistency across campuses and challenge the notion that victims must have resisted assault to have valid complaints.

"This is amazing," said Savannah Badalich, a student at UCLA, where classes begin this week, and the founder of the group 7000 in Solidarity. "It's going to educate an entire new generation of students on what consent is and what consent is not... that the absence of a no is not a yes."

The bill requires training for faculty reviewing complaints so that victims are not asked inappropriate questions when filing complaints. The bill also requires access to counseling, health care services and other resources.

When lawmakers were considering the bill, critics said it was overreaching and sends universities into murky legal waters. Some Republicans in the Assembly questioned whether statewide legislation is an appropriate venue to define sexual consent between two people.

There was no opposition from Republicans in the state Senate.

Gordon Finley, an adviser to the National Coalition for Men, wrote an editorial asking Brown not to sign the bill. He argued that "this campus rape crusade bill" presumes the guilt of the accused.

SB967 applies to all California post-secondary schools, public and private, that receive state money for student financial aid. The California State University and University of California systems are backing the legislation after adopting similar consent standards this year.

UC President Janet Napolitano recently announced that the system will voluntarily establish an independent advocate to support sexual assault victims on every campus. An advocacy office also is a provision of the federal Survivor Outreach and Support Campus Act proposed by U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer and Rep. Susan Davis of San Diego, both Democrats.