Federal officials say the sickest 5 percent of Americans rack up more than half of all health care costs.

This small group of people often have chronic health conditions, and have high rates of emergency room visits and hospitalizations.

A San Diego program is attempting to teach these “high utilizers” how to navigate the healthcare system, break the cycle of crises and manage their own conditions.

The approach is labor intensive, but program officials say it actually saves money.

Take LaShawn Encarnacion, for example. The 39-year-old has a boatload of chronic health problems.

“Type two diabetes, extreme morbid obesity, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, high blood pressure,” he recounted.

And that’s just the physical stuff.

“And then of course we go into the depression," Encarnacion said. "My official diagnosis is borderline personality disorder.”

Encarnacion has had a tough time the last few years. About every three or four months, he’s gone to an emergency department. He’s also been hospitalized.

Encarnacion has health insurance, but he’s run into plenty of red tape and denials of care. But lately, he’s been getting some help.

Social worker Alicia Asaro is helping Encarnacion get the benefits he’s entitled to, and get his health under control.

"The mattress, the walker and the cane, all of those things, we’re gonna start working through it." Asaro told Encarnacion as they sat in her southeastern San Diego office. "And then you had therapy yesterday, right?”

Asaro is part of a care management team that’s at the heart of a program called the Patient Health Improvement Initiative. This grant-funded program targets chronically ill patients who lurch from one crisis to another, often ending up in the hospital and racking up enormous costs.

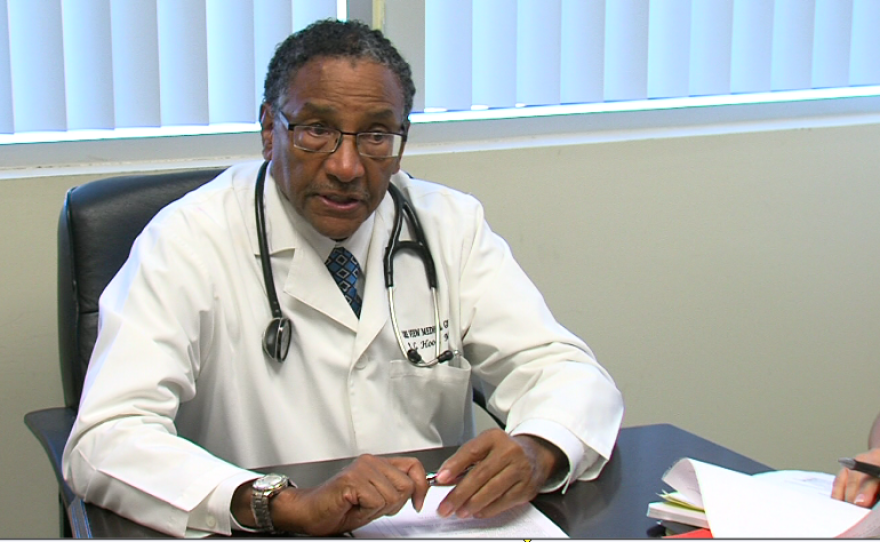

Rodney Hood heads up the initiative.

He said in some ways it’s similar to Project 25, an effort that finds housing and seeks to improve the health of homeless San Diegans.

But Hood said the majority of patients in his program have housing and insurance. They live in areas of the county, like southeast San Diego and National City, which have the highest rates of ER and hospital visits.

“They’re going to the ER because of what we call social barriers," Hood explained. "There’s problems of lack of education, lack of transportation, food problems, not understanding the medications, not being able to get with their coverage to get the benefits that they have.”

Hood said his team works closely with each patient for up to a year. They help stabilize the patient, and address the social barriers affecting their health. In essence, the team teaches patients how to improve their quality of life.

“Not necessarily holding their hands, but teaching them and empowering them how to navigate into a better future,” he said.

The template for Hood’s program was created in 2007 in Camden, New Jersey. A doctor named Jeffrey Brenner used raw billing data from three Camden hospitals to identify high utilizers of health care.

“We learned that 20 percent of the patients were 90 percent of the cost," Brenner said. "Someone had actually gone to the emergency room 113 times in one year."

Brenner explained instead of waiting for people to show up at the hospital, he formed a team to actively seek out chronically sick people and take better care of them. Using this unique approach, Brenner’s team was able to cut hospital visits and costs in half.

In 2012, Hood received a federal grant to fund a similar program in southeastern San Diego. So far, they’ve enrolled a total of 124 patients. The effort is the only federally-funded program of its kind in California.

And so far, it has achieved some impressive results. A cohort of 21 patients from one health plan slashed their medical costs from $1.6 million to $960,000 in one year. Even when you factor in the costs of Hood’s team, that’s a 40 percent savings.

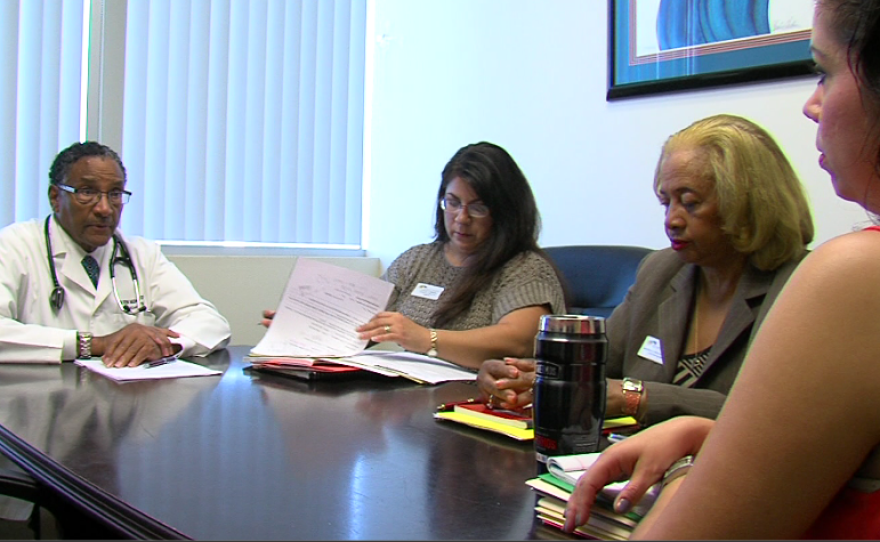

The team meets twice a week to discuss cases and new referrals. They currently handle 26 patients.

Nurse case manager Montrula Donaldson said the biweekly meetings are absolutely essential.

“We’re all there, and we’re talking together, and then we can see: okay, what do we need to do more for this patient," Donaldson said. "Or, is this patient done, have they met their goals? That’s one thing that we do when we admit them, is we set goals for them.”

After patients are transitioned out of the program, volunteers call them once a week to make sure they stay on track.

Lavella Picou, who lives in El Cajon, recently “graduated” from the program. To be sure, she still has severe health problems, including a bad hip and sickle cell disease.

But thanks to the program, Picou stays on top of her medications, and has greatly reduced her need for transfusions.

“I’m not sick all the time, so I wake up happy now," Picou said. "Usually I would wake up, I can’t get out of bed, my blood’s low. When your blood’s low, you’re really tired. Now I know I have them on my side, so I can call for help if I needed it.”

LaShawn Encarnacion has only been in the program about a month. He’s really concerned about his health. But now that he’s working with the team at the Patient Health Improvement Initiative, Encarnacion said he can imagine getting better.

“I just want to be a productive member of society. Earn a living, have my own apartment, maybe my own home and just, live a life that most people have,” he said.

The program’s funding runs out next year. Hood said he’s asking insurance companies to underwrite it, since they’re the ones reaping the most savings.