For many years, Robin Williams seemed like a talent who had no off switch.

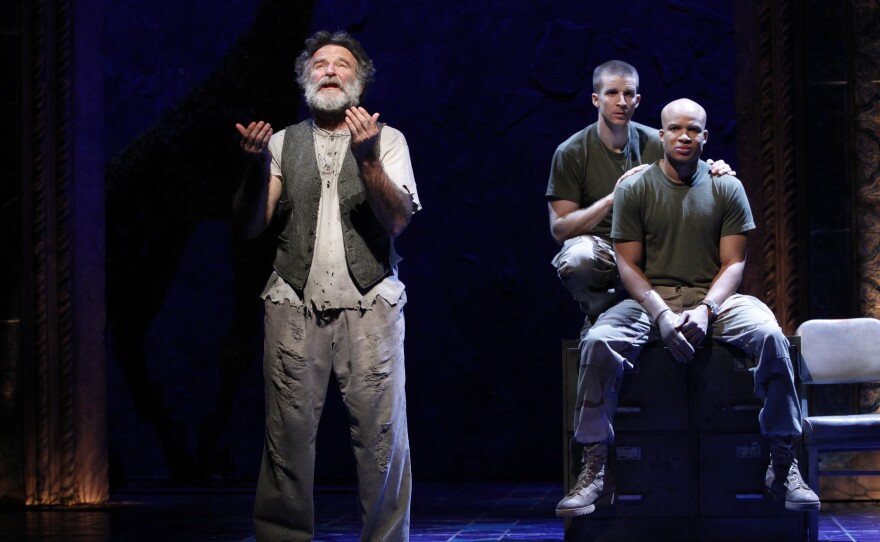

From his standup comedy work to TV roles to talk show appearances to Oscar-caliber movies and performances on Broadway, Williams was a dervish of comedy — tossing off one-liners, biting asides and sidesplitting routines in a blizzard of accents, attitudes and goodhearted energy.

But that long legacy of entertainment ended Monday, when Williams, 63, was found dead in his home. A statement from the Marin County, Calif., Sheriff's Office says they suspect the comic, who had been battling depression and had recently spent time in rehab, died by suicide due to asphyxia.

Williams' death drew expressions of shock and sympathy from across the country, as celebrities including Ben Stiller, Howie Mandel, Jane Lynch, Simon Cowell, Roseanne Barr and Chelsea Handler tweeted condolences alongside information on suicide hotlines.

Even President Obama weighed in, with a statement saying, in part: "Robin Williams was an airman, a doctor, a genie, a nanny, a president, a professor, a bangarang Peter Pan, and everything in between. But he was one of a kind. ... The Obama family offers our condolences to Robin's family, his friends and everyone who found their voice and their verse thanks to Robin Williams."

"It's always sad when a comedian dies," comic Joy Behar, a longtime friend of Williams, told CNN Monday night. "It's sad to me that someone who could bring so much laughter and pleasure to others could not do it for himself. He was a tortured soul, I think."

Williams seemed the kind of performer who would always be at the center of show business, with a career that included some of the most iconic films of the '80s, '90s and beyond: Good Morning Vietnam, The World According to Garp, Dead Poets Society, Awakenings, Good Will Hunting, Aladdin, Mrs. Doubtfire and The Birdcage, to name a few.

His achievements would eventually include three Best Actor Oscar nominations and a win as supporting actor (for Good Will Hunting), along with an enduring legend as one of those rare talents who could succeed in both comedy and dramatic parts.

And his roles touched fans deeply across generations — whether it was kids who loved his work as a madcap alien on the 1978 sitcom Mork & Mindy or children who fell for his performances in the animated comedy Happy Feet 28 years later.

Who else could have played a wisecracking radio DJ in Vietnam, an introverted Parkinson's researcher and Peter Pan, all within four years of each other?

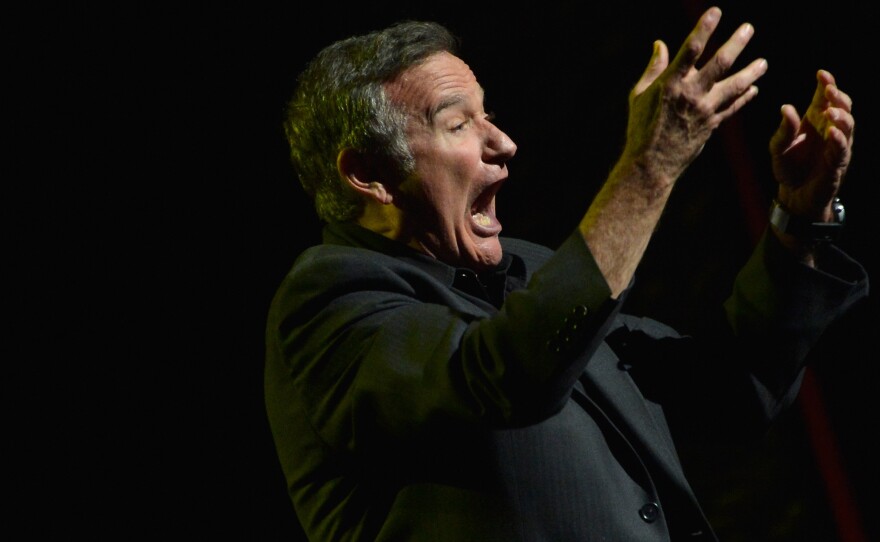

His comedy work was the polar opposite of comedy craftsmen like Jerry Seinfeld, famous for obsessing over every turn of phrase in a bit like a careful carpenter. Williams tossed jokes out like a machine gun, spraying comedy in a fountain of ideas guaranteed to connect, one way or another, with just about everyone in the audience.

But his towering career started on the small screen, playing an oddball alien character called Mork from Ork on the '70s-era ABC sitcom Happy Days.

On paper, Mork was the kind of character that often signaled a show was ready for cancellation; an extraterrestrial dropped in the middle of a family sitcom set in the 1950s. Williams — Juilliard-trained but with a resume including a stint on the short-lived Richard Pryor Show — used Mork's strange origins and stranger attitude to channel his own unique comic id, building a new alien race out of a batch of funny accents and playful imagination.

Back then, Williams' work on Happy Days and the successful spinoff Mork & Mindy, along with sidesplitting turns on The Tonight Show and his standup comedy album Reality...What a Concept, left little doubt that a new comic voice had arrived.

And it was a popular one; the Mork character spawned catchphrases and loads of merchandising, launching Williams as a superstar who already seemed a bit too big for the small screen.

With lots of deference paid to comedy predecessors like Jonathan Winters and Red Skelton, Williams was a comic ready-made for the MTV generation — rapid-fire wit, with a taste for naughty subjects and openness about his own problems that felt right in step with the times. Cocaine, he often joked, "was God's way of saying you're making too much money."

In movies, Williams toggled between roles fueled by his comedic talent — Good Morning Vietnam's iconoclastic Armed Forces Radio DJ Adrian Cronauer or the fast-talking genie in Aladdin — and more measured dramatic parts like the therapist pining for his dead wife in Good Will Hunting or the passionate boarding school English teacher in Dead Poets Society.

(I particularly enjoyed seeing Williams turn his talent to playing villains, particularly the creepily obsessive photo tech in One Hour Photo and the Alaska-based killer in Insomnia.)

He even brought a burst of stardom to NBC's gritty police drama Homicide: Life on the Street in 1994, earning raves for his portrayal of a tourist whose wife was killed by a gunman in the show's second season premiere.

And his Comic Relief charity specials with Billy Crystal and Whoopi Goldberg were also landmark television on HBO, raising many millions while featuring the sharpest comics around in a comedy version of Live Aid starting in 1986.

Throughout his career, however, there was a sense of a talent who had trouble turning off his gifts. Appearances on talk shows and red carpets could be as manic as his professional performances. He struggled with substance abuse for much of his time as a superstar and checked himself back into a rehab facility in July to better focus on his sobriety, according to his representatives.

By his last TV series, the 2013 CBS comedy The Crazy Ones, there was a sense that a bit of the magic was missing. Fun as his energetic routines could be, his role as an unpredictable ad man seemed like a road we'd all seen him walk too many times before; CBS canceled the show after its first season ended this spring.

Still, Williams retained his status as the world's jester — an endlessly entertaining performer whose greatest acting role just might have been masking the emotional pain that eventually cut his life short.

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/