UPDATE: Frida Kahlo Exhibit Organizers Respond To Criticism

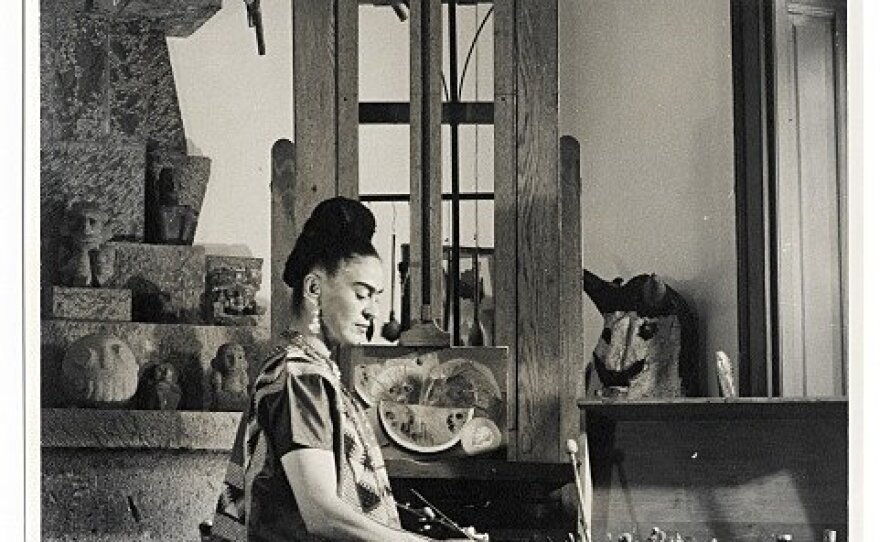

Banners as tall as the building hang from the roof of Barracks 3 at the Naval Training Center at Liberty Station in Point Loma. On each is a familiar portrait of the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. She’s dressed, as she often was, in traditional Mexican clothing. She stares directly at the camera from underneath her famous unibrow.

The banners announce the exhibit inside, titled: “The Complete Frida Kahlo: Her Paintings, Her Life, Her Story.” She was a compelling figure and her paintings detail her dramatic life and marriage to Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

Any exhibit about Frida Kahlo is likely to draw audiences, but this latest one is also drawing controversy.

All of Kahlo’s paintings (123) are in this show, but none of them were actually painted by her. And from the banners, advertisements, even the catalog that accompanies the exhibit, the audience is none the wiser.

The paintings on display are replicas of Kahlo’s work. They were commissioned from four Chinese artists who are not credited. Yet the press release announcing the exhibit says, “This is the only exhibition worldwide where all of her paintings can be seen in one place. Some paintings, especially from Kahlo’s early years, have never before been seen.”

Hugh Davies, David C. Copley director and CEO of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD), didn’t mince words when asked about the exhibit, on view through mid-January.

“To have a show entirely of copies and to promote it as all Frida Kahlo’s paintings together for the first time is completely dishonest,” he said.

The Kahlo exhibit is the masterpiece and passion of Dr. Mariella Remund and her partner Hans-Jürgen Gehrke. Neither of them has an arts background but together they’ve put 30 years into this project.

They conceived it, hired the Chinese artists and staked their life savings on it. Why?

“Because we are crazy,” Remund said. A former top executive at Dow Chemical, Remund is tiny and wears her jet black hair in a blunt bob with bangs.

“We are crazy about Mexico and the Mexican culture. We are crazy about Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera,” she explained. “And there was a point five years ago when we decided we were ready to share our passion with anyone who is interested.”

They paid the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust for the rights to copy the paintings.

The couple established a private museum, the Kuntsmuseum Gehrke-Remund in Baden-Baden, Germany, where Kahlo’s father was born. They partnered with Global Entertainment Properties 1, LLC (GEP1) to take the collection on tour. The Los Angeles-based entertainment company has produced touring exhibitions about Star Trek and the movie, Titanic.

San Diego is the first U.S. stop for the Frida Kahlo exhibit, but it’s gaining a dubious reputation that might precede it as it makes its way across the country.

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

A fine art show made up entirely of replicas is unusual. But the bigger issue is one of transparency.

On a recent Friday, Carol Morrison and Marlene Gotz walked through the exhibit using the companion catalog as a guide.

When asked whom they thought painted the artwork on the walls, Morrison looked surprised. “Is there a question as to whether she painted them or not?” she asked.

A woman nearby overheard the explanation that the paintings were replicas and walked over. “Even the ones with Frida Kahlo’s signature?”

As they turned to leave they said it didn’t matter. They were enjoying the show anyway.

So, does it matter that the exhibit and its promotional materials don’t mention the word “replica?”

Curators and fine arts experts say it does.

“It bothers me that I did not see the word replica there,” said Roxana Velazquez, executive director of the San Diego Museum of Art, after visiting the exhibition.

Traditionally in a museum or gallery exhibition, there would be an introductory text on the first wall explaining the show. This would be an ideal place to make it clear that the paintings are replicas and give attribution to the Chinese artists.

“If you’re walking in and not understanding that these are copies, it is giving a false presentation to the viewer and the audience,” says Alessandra Moctezuma, a fine arts professor who teaches museum studies at San Diego Mesa College.

There is an 8.5-by-11-inch sheet of paper taped to the ticket counter and the door of the exhibit. In two sentences it explains that the paintings are replicas. People walked by without reading it.

Remund said she wasn’t concerned people might think the paintings are originals.

“We were not (worried), because we always said in all of our communication they are replicas. From our point of view, it’s written everywhere. It’s in the advertising. It’s in every possible piece of communication,” Remund said.

It’s not on the banners or brochures. It’s mentioned only once in the 48-page companion catalog, in reference to “The Wounded Table,” painted by Kahlo in 1940. The original disappeared on its way to an exhibition in Moscow in 1955. In the catalog it explains that the organizers researched the missing painting for three years before “having the painting replicated.” The jewelry and clothing in the exhibit are often described as reproductions, but not the paintings.

In a subsequent interview, Remund conceded there was no statement explaining the paintings were replicas in the catalog or in other materials.

“You’re right,” Remund said. “This is the exhibition highlight and you are right and we’re going to correct it in the next edition. This is the result of work done under pressure, that’s all. “

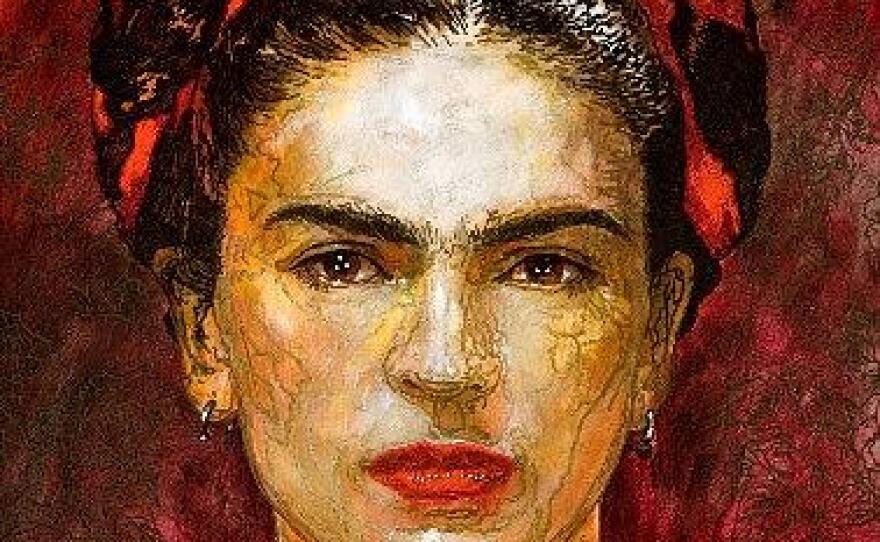

Pressure or not, all 123 paintings in the catalog are identified with the specifics of the original Frida Kahlo paintings, not those of the copies. For example, the painting in the exhibit No. 25 is listed in the catalog this way: “Self-portrait, 1930. Oil on canvas, 65 x 54 cm, Private Collection, Boston, Massachusetts.” From this information, a viewer might logically assume the painting they are looking at was painted in 1930 by Frida Kahlo and is on loan from a private collection in Boston.

Moctezuma thinks the word replica should be placed next to the title of each painting, along with credit to the Chinese artist who painted it.

“That for me is an issue of misrepresentation,” she explained.

Online information about the show might be the most transparent. In the event listing on San Diego.org it states: “the exhibition features 123 replicas of her [Kahlo’s] known paintings in original size and original materials, and hand-painted in the same style as Kahlo painted them.” This information is also on the very first page of the exhibit’s website.

Remund explained there is another safeguard in place to ensure visitors understand the paintings are replicas. In the gift shop, which is also the exit, an employee always asks visitors how they liked the show, according to Remund.

“There is the chance for anybody to ask, ‘How did you put together all these originals?’ And then we say it. That these are not originals, of course, they are replicas,” she said.

Andy Gonzalez owns the La Onda Arte Latino gallery at Liberty Station. He specializes in selling Chicano and Latino art. He sells a poster of a Frida Kahlo painting by East Los Angeles muralist George Yepes.

Gonzalez has guided tours through the Kahlo exhibit and thinks it’s a great introduction to Kahlo’s life.

“It’s like a history book,” he said.

Gonzalez said he’d be surprised if anyone thought Frida Kahlo’s actual work would be on view in an old army barracks.

“Most people that know anything about Frida or art know that [such a show] would be a in a big name museum,” Gonzalez said. “It would be under lock and key and under guns and everything else to guard it.”

The Kahlo Painters

There is a tradition in China of painters learning their craft by copying master works. It would be a logical place to source quality copies of artwork.

Remund said there is a reason why the Chinese artists aren’t named or given credit in the exhibit.

“We are so proud of our artists and what they have done. We wanted to present them on our website with their biography but they didn’t want to because they didn’t want to be known worldwide as the artists who replicated Frida Kahlo,” Remund said. “They want to be known for their own work.”

According to the exhibit’s website, the artists live and work in an artist colony in China called Song Zhuang.

Remund lives in Beijing, so it was easy to hire Chinese artists to copy Kahlo’s work.

According to her, it took the four artists one year to copy most of Kahlo’s paintings. A couple of paintings took two years, and one took three.

The artists were sent to Mexico City, New York and Paris to research the originals, Remund said, all on her dime.

“We could have retired in the south of France with a villa and two Ferraris, but we decided we would rather do this,” Remund said.

She visited the artists at their studios almost daily to monitor their progress. She and Gerhrke gave the artists research-filled binders and explained the technical and emotional aspects of each painting.

“How Frida felt at that specific time, why she painted it, how she wanted to express herself and what was around in her life,” Remund explained.

To a trained eye, the fact that the show was produced by four artists is obvious.

“You can tell immediately that these are not works done by one single hand,” said Velasquez, of the San Diego Museum of Art. She’s from Mexico City and has organized shows about Frida Kahlo. She commented on the quality of the reproductions.

“If I had to pick a word, I would have to say it’s an uneven quality,” Velasquez explained.

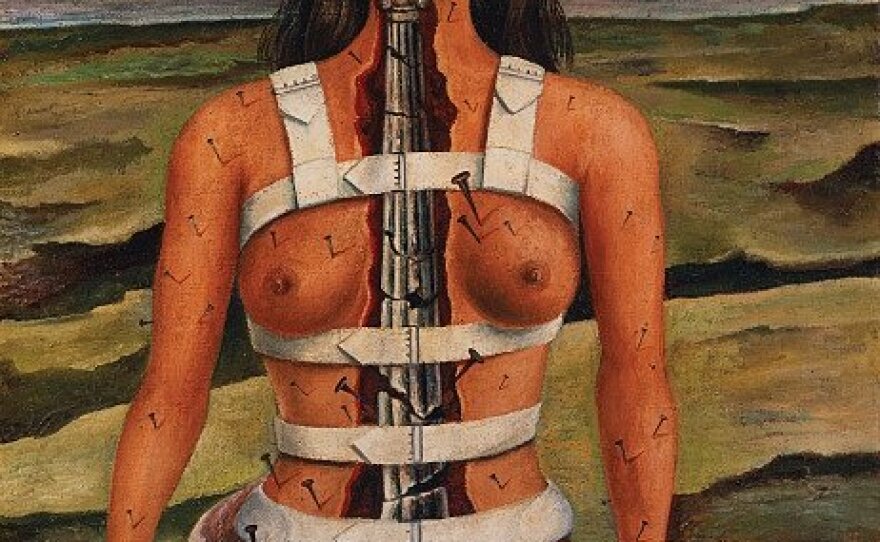

She said some of the still life paintings are good, but some of the self-portraits are not. Velasquez cited “The Broken Column” a self-portrait painted in 1944 shortly after Kahlo underwent spinal surgery. She’s nude and wearing a binding metal corset. Her spine is visible through a rift down her center. Kahlo painted it to show her physical and emotional suffering. The original, Velasquez said, achieves that brilliantly, especially in the depiction of the eyes. But the replica does not.

“You see the tears, but you don’t feel the mourning,” Velasquez said.

Moctezuma explained there’s a reason museums, scholars and conservators are so concerned about authenticity and provenance.

“A painting is not only a work of art, it is also an historical document,” she said. “Embedded in it are all the hours spent by the artist producing it, the layering of the brushstroke, and all the changes that happened. It’s a whole intellectual process, not just a manual process.”

Hugh Davies, director of MCASD, said he’d rather see a good photographic reproduction of a painting than a copy. When we spoke, he had not yet seen the show. “Because at least with a good photographic reproduction, we all know how to make that shift from a photograph of a painting to an actual painting.” He added, “We know that the texture and the colors aren’t always accurate.”

The Show’s Future

Tucson residents Anna and Scott Griessel went to see the exhibit while visiting San Diego. They loved it.

“It seems like a pretty genuine experience even though you know they are reproductions,” Scott Griessel said. “Having all of her paintings together like that really gives you a strong sense of who she was.” Anna agreed. “I was skeptical at first, because I saw on the website that they were replicas, but it was really interesting.”

Marlene Gotz, one of the women who learned the paintings’ origins from this reporter, said the exhibit “is magnificent.”

Tickets cost $16.50. That’s a price point often reserved for blockbuster museum exhibits, though it is on the low end of that scale.

Though San Diego is the premiere, the organizers’ partner in this endeavor, GEP1, did explore other venues for “The Complete Frida Kahlo” in cities like Los Angeles.

Jose Antonio Aguirre is the executive director of the Mexican Cultural Institute of Los Angeles, located on Olvera Street in the heart of Los Angeles. He said they were approached but declined, in part, because much of his audience could not afford the ticket price.

Remund said they are exploring options for the next stop on the exhibit’s tour. They are planning to go east, possibly to Texas.

Remund remained undeterred by the controversy surrounding the San Diego leg of the exhibit.

“We were not even worried that people would accept it or not because we learned in life that one cannot please everybody,” she said. “This is our true passion and we share it with whoever has an open mind and wants to come see it.”