So maybe the Great Recession really is over.

After more than five years of recession and painfully slow recovery, President Obama has sent a powerful signal that he thinks the U.S. economy is now in much better shape -- good enough, at least, to provide workers with raises.

In his State of the Union address Tuesday night, Obama called upon Congress to boost the federal minimum wage to $9 an hour by 2015, up from the current $7.25. The wage would rise in steps, and after hitting the maximum in two years, would thereafter be indexed to inflation.

In the president's first term, the unemployment rate was very high, peaking at 10 percent in October 2009. And during those four years, Obama never seriously pushed Congress for legislation to force employers to pay more.

Tuesday night, he changed direction, saying in his State of the Union speech that he wants Congress to drive up wages for millions of workers by forcing up the benchmark minimum wage. Even though only a relatively small percentage of workers make $7.25 an hour, that pay level serves as a wage floor for all workers. When it moves higher, other wages ratchet up too.

In other words, if Congress were to boost the minimum hourly wage, then a person currently making $9 likely could move up to $10 or even $11 an hour as employers adjusted pay scales to higher levels to compete for the better low-wage workers.

'Honest Wages'

The White House says 15 million workers would benefit directly from a higher minimum wage, but many economists say that millions more would gain too after taking into account the ripple effect as the whole wage scale moves up.

"We know our economy is stronger when we reward an honest day's work with honest wages," Obama said. "But today, a full-time worker making the minimum wage earns $14,500 a year."

He said that's not enough money to keep a family above the poverty line. "Let's declare that in the wealthiest nation on Earth, no one who works full time should have to live in poverty, and raise the federal minimum wage to $9 an hour. This single step would raise the incomes of millions of working families."

The president's focus on the minimum wage came as something of a surprise, even to longtime supporters of a pay increase. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., said in an interview Wednesday morning that while she agrees with the president, "I didn't know he would bring it up."

Given that the wage push was unexpected, she said she did not know how Democratic lawmakers might put together their strategy for getting the legislation passed. For many years, it had been Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Edward Kennedy who led congressional battles for higher wages. But with his death in August 2009 -- one month after the last minimum wage hike took effect -- supporters will need a new champion in Congress to marshal the troops.

Opponents already are gearing up for the fight. At a press conference this morning, House Speaker John Boehner, a Republican, made it clear he would work against minimum-wage legislation.

"When you raise the price of employment, guess what happens? You get less of it," Boehner said. "At a time when the American people are still asking the question, 'Where are the jobs?' why would we want to make it harder for small employers to hire people?"

Congress last passed a bill establishing a series of minimum wage increases in 2007 -- before the Great Recession began. The last of those increases took the pay up to $7.25, where it has remained frozen.

Higher Existing Minimums

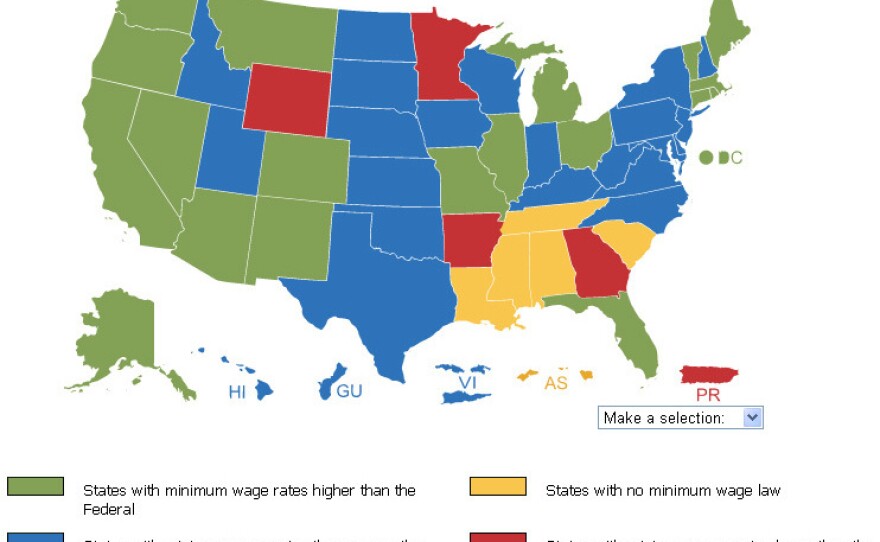

Nineteen states plus the District of Columbia have minimum wages above $7.25. For example, in Washington state, the pay is now up to $9.19 an hour -- the highest minimum in the country. If the federal level were to rise, many of those 19 states would most likely pass new legislation to exceed it.

If the past is any indicator, business groups -- particularly the National Restaurant Association -- will put up a fierce fight to block any federal minimum wage increase.

Another group backed by the restaurant and hotel industries says an increase in the minimum wage can hurt the economy. "The President's minimum wage hike ignores both simple economic logic as well as the overwhelming scholarly consensus on minimum wage hikes," Michael Saltsman, research director of the Employment Policies Institute, said in a statement. The institute says research "points to a loss of job opportunities following a minimum wage hike."

But many economists point to studies that show a higher minimum wage does little to hurt job creation. Instead, these economists argue that a higher wage reduces income inequality and puts more money into the hands of the consumers who can spend it. So, the argument goes, while a pizza-shop owner might have to spend more on his payroll under new wage legislation, he also would see a boost in revenues as customers find themselves enjoying bigger paydays.

A Hot-Button Issue

The minimum wage has been a hot-button issue with business groups since its introduction in 1938. They argue that a federal minimum wage is inflationary and represents an unnecessary government intervention in the labor market. They say labor supply and demand alone should set wages, not lawmakers.

Supporters disagree. They say inflation is very low, while income inequality is growing. Working people lack of spending power, and that's what is inhibiting economic growth, the argument goes.

"We applaud the president for expressing support for raising the minimum wage and tying it to the cost of living," Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, said in a statement on behalf of the labor organization. He said the economy is not suffering from high wages but rather from "wage stagnation and growing inequality."

Between 2000 and 2010, U.S. median income fell 7 percent after adjusting for inflation, according to census data. Over the past year, the unemployment rate has hovered at or just below 8 percent.

Copyright 2013 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.