painful to keep talking about the elementary school tragedy in Connecticut. There is no conclusion at this point that the shooter suffered any mental instability, but it's impossible to imagine a healthy, well-balanced human being doing what he did. It should be noted that only about 4% of violence in the United States can be attributed to those with a mental illness, that's according to the American journal of psychiatry. Today, we're going to talk about Laura's law, a California law passed ten years ago that addresses individuals who threaten to be a danger to themselves or others. And our guests are doctor Michael Plopper who has been the sheave medical officer of sharp healthcare behavioral health services. Thanks for being here. PLOPPER: Thank you. ST. JOHN: And Piedad Garcia, assistant deputy director of San Diego County's Adult Mental Health Services. Good afternoon. GARCIA: Good afternoon. ST. JOHN: Michael, tell us, what is Laura's Law? PLOPPER: Laura's Law was passed about 10 years ago, through the California Legislator, and in part as a consequence of the murder of a young woman in Northern California by a person who had untreated schizophrenia. And part of the law provides for assisted outpatient treatment for persons who have severe mental illness, who can be determined to have the potential to be a danger to themselves or others, have a documented history of mental illness or incarcerations, and each county has a choice to implement it or not. It was passed after a lot of discussion and multiple votes to get into treatment people who have serious illness and have no insight into their illness and may have the potential to ve a danger to themselves or others. ST. JOHN: And how many counties in California are actually using it? PLOPPER: Currently it's only used in Nevada county, where Laura was killed. And quite successfully in that that county, and also in Los Angeles county on a more limited basis. ST. JOHN: So apparently the county mental health board which advises the county, the Board of Supervisors on health policy, they voted in behavior of adopting Laura's law here last year. Why did the county health department decide against implementing it? GARCIA: There were several reasons. And one of them certainly had to do with having a service model or treatment model that is much more inclusive and participatory rather than an involuntary model of treatment. Secondly, we also felt that there was a financial burden associated with the implementation of Laura's law here. In relationship to not only the treatment service but the Court services and all of the multiple stakeholders that would have to put into place Laura's law. Certainly it would also create a burden for the hospital system in terms of having to follow through with the court order since these individuals would have to have had if not incarceration hospitalizations to implement Laura's law. ST. JOHN: My understanding of it is it doesn't necessarily mean incarceration, right? It's more outpatient treatment and medication, right? GARCIA: Right. It would be a choice. For the client to be in jail or -- ST. JOHN: I see. GARCIA: Choose treatment. The last reason was also the protection of the individuals' rights, that we were also concerned about, and we thought that after stakeholder input, and balancing the pros and con was this implementation, that we would provide an alternative to Laura's law. And the outreach team is the alternative that we've implemented over the past year. ST. JOHN: Talk about what San Diego is doing, this in-home patient treatment. GARCIA: Yeah, we also have a compliment of other intensive treatment programs that serve individuals who have a serious mental illness and are very, extremely difficult clients. And these full-service partnerships are 24/7 outpatient treatment services. And it's really staff per client. Going to IHOT, it's a prevention, early intervention program. It's an innovative program -- ST. JOHN: And one of the clear distinctions between it and Laura's law is that it doesn't force anybody to go through treatment, right? GARCIA: Correct. ST. JOHN: So this is a voluntary treatment program. GARCIA: And actually, it's not even treatment. It's an outreach engagement team of individuals that go into the home of the participant, not client or patient, and really about half of the referrals come from parents. So they seek out the team to come into the home to begin in outreach and engage the individual who is perceived as treatment resistant, who is perceived as having a serious mental illness. And over the past year, we have seen a great success with the program, we have UCSD is doing the evaluation of this component, and about -- probably about 40% of the clients or participants in the program that were at one point perceived as treatment resistant have engaged in the service of the IHOT team, which is provided by clinicians and case managers in the home and also by peer and family coaches that go into the home to assist the family and the participant with whatever it is that they need. ST. JOHN: Now, there was an excellent article in the Huffington Post by a very brave mother who writes about how she was forced to take her son to the hospital when he threatened to kill her and himself just once too often. A very moving article, I highly recommend it. If a troubled parent contacts you with a child threatening to kill them, is this the program that you would refer them to? GARCIA: Actually when there is a threat to somebody's safety, I would call 911, and I would recommend that the family member calls 911. And usually what they do is connect with the PERT team, which is an officer and a clinician which would come to the home and respond to that emergency. ST. JOHN: That's another program. GARCIA: Correct. ST. JOHN: Michael, how do you respond then to critics who say that, you know, perhaps this program doesn't have enough teeth or is too expensive to implement, the Laura's law? PLOPPER: Well, I think the law itself has adequate teeth, so to speak, if it were to be implemented. I think that we really could reach people who otherwise would not avail themselves of IHOT. I think IHOT is a great program. ST. JOHN: It's the one that may not have enough teeth, perhaps. PLOPPER: It's the one that doesn't have enough teeth, I believe, for certain people who have serious psychotic disorders. It's really the person who has a serious mental illness including dilutions and hallucinations, generally with severe schizophrenia and who does not have insight into their illness and are not willing to seek treatment that really need to be reached and treated. They're the ones that can be dangerous. I think we worry about talking about the potential for violence among the mentally ill because we really don't want to further stigmatize the mentally ill any more than we already have, we in mental health experience. ST. JOHN: Right. PLOPPER: But from my perceive, a person who has untreated mental illness and stays in that condition for a long, long period of time suffers personally far more stigma than were they to be in treatment functioning reasonably well and a member of society. So I think that for the individual, the personal stigmatization is far less if they're in treatment. But what Laura's law does is allow for those very resistant potentially dangerous people to get care. ST. JOHN: Laura's law is obviously a little stricter, perhaps, or more compulsory than anything that San Diego County has in place right now. What about this PERT program? Do you think that rises to meet the need here? PLOPPER: Well, are the PERT program is a marvelous program in this county in which a mental health clinician rides along with a police officer and responds to situations in which a person may well have a mental disorder and is coming in contact with law enforcement. It's a great way to avoid negative interactions between the mentally ill and police officers. Because the clinician can intervene and get the person in the right place. But that is a methodology to go out and get someone and take them to treatment. ST. JOHN: Uh-huh. PLOPPER: Who may meet the criteria for a 72 hour hold. That would be something that would be utilized with Laura's law as a methology. ST. JOHN: Okay. PLOPPER: If a person was not following recommended treatment. ST. JOHN: So when you look at the fact that there might be a place where neither of these programs that San Diego has in place, would prevent some kind of a tragedy, like, that's what we're sort of talking about today, is prevention. What about the idea that in fact that is more important than -- you talked about respecting the individuals' rights, and obviously that is key. And I know you've done a lot of work to make sure that those with emotional issues were not being targeted and stereotyped. But when you look at what the risks are, does it seem like there is an argument now for adopting Laura's law in San Diego? GARCIA: The issue of protecting one's right in the larger context is a delicate balance. In making an ultimate decision as to implementing Laura's law. I think that we have programs like mental health courts, drug courts, behavioral health services courts already in place that are court ordered treatment rather than jail or involuntary hospitalization. We have the 5150 law. That gives the opportunity for individuals to -- who are in imminent danger to be taken to a hospital for an involuntary psychiatric hospitalization upon evaluation. And of course the PERT team. And the office of the conservator. We do have in place, laws and programs that can certainly intervene and minimize the potential danger for such tragedies. Now, there is not a fail-proof law or service or program that can predict or prevent violent behaviors and tragedies such as the ones that we just experienced. ST. JOHN: So you don't believe that Laura's law would even make much of a difference in this? GARCIA: It would capture a culprit of small number of individuals, but that does not mean that it will prevent all the potential possibilities that are there. ST. JOHN: You mentioned that one of the reasons that you did not adopt it was the cost. And I understand that it would probably cost about $2 million. And the IHOT team is costing about -- GARCIA: $1 million. ST. JOHN: So we would be talking about $1 million extra, when you look at the county's budget is really not a lot of money, is it? GARCIA: Right. ST. JOHN: How significant is that cost? A report from LA County, a study found that Laura's law significantly reduced hospitalization rates. GARCIA: The cost that you just mentioned are only the service costs. That does not include the cost associated with the Court and probation and police and so on to implement Laura's law. So the numbers don't equate there, actually. ST. JOHN: I see. Okay. I just want to throw one last question to you, Michael, whether you feel there's likely to be anymore discussion in San Diego County about whether this law would be a good addition to our array of options of working with people. PLOPPER: Well, I would hope so. I believe had it really does provide at least a partial solution to this issue. She mentioned the behavioral health court which is I fantastic program, it's new. It service a relatively small number of people, unfortunately, so far. But those people need to have committed a criminal act to be served by that court. ST. JOHN: Ah, that's the catch. PLOPPER: So we're talking about getting into treatment those people who could commit a criminal act but haven't yet and need treatment. Additionally, she mentioned the conservator's office, that's restricted to people who are greatly disabled and they can't provide food, clothing, and shelter for themselves. We're talking about dangerousness for others, not grave disability. So the conservator's office, while it is a very important component of treatment in our services in this community does 7 only that population. ST. JOHN: And I believe you say implementing it in San Diego County would reduce healthcare costs. PLOPPER: I believe that to be true. ST. JOHN: Well, are it's a good thing to be raising. And just a quick chance for anybody who's listening out there who feels like they actually need to ask for help, you have a hotline number. GARCIA: Sure. It's 1-888-724-7240. ST. JOHN: And this'll be on our website. And there's another website, UP2SD.org, a Good place to go if you're looking for help from the county. Thank you so much.

San Diego County Mental Health Resources

Crisis line: 1-888-724-7240

Psychiatric Hospital of San Diego County

San Diego County Office of Violence Prevention

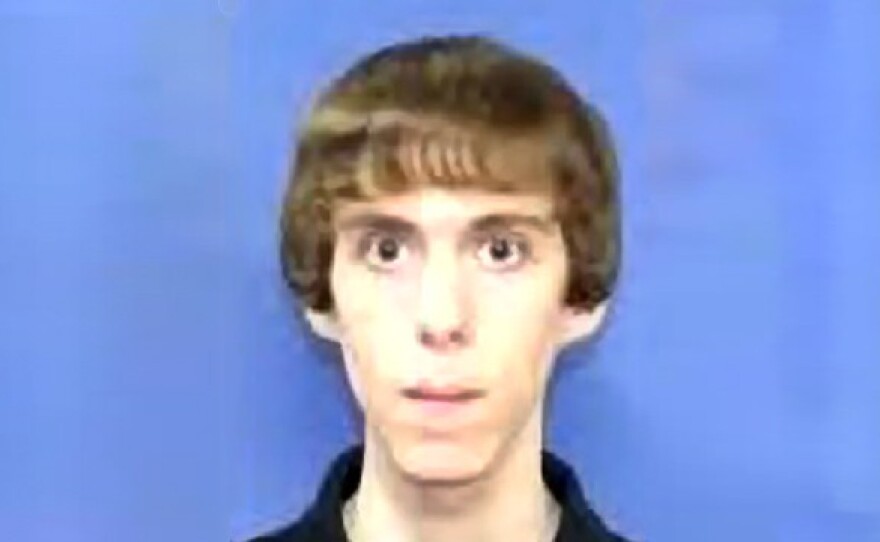

The school shooting in Connecticut has sparked a national dialogue on what can be done to treat people with mental illness. While it is not known whether the gunman, 20-year-old Adam Lanza, suffered from a mental illness, there have been several reports that he had a developmental disorder.

In California, Laura's Law would allow court-ordered outpatient treatment to people who show they could be a threat to themselves or others. Counties can opt in or out of implementing the 2002 law. Only one county in the state, Nevada County, has opted into the law. Los Angeles County has implemented Laura's Law as a pilot program.

San Diego County's Mental Health board voted in 2011 to implement Laura's Law, but the San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services decided not to implement the law.

Piedad Garcia, the assistant deputy director for one of that department’s programs, told KPBS they decided not to pass the law for a number of reasons, including costs and not burdening hospitals.

"The protection of the individual’s rights that we were also concerned about," she said. "And we thought that after stakeholder input and balancing the pros and cons of this implementation, that we would provide an alternative to Laura’s Law."

Instead, the county's behavioral health department chose to implement a different program, the In-home Outpatient Treatment or IHOT, in January 2012.

Alfredo Aguirre, behavioral health director for San Diego County Health and Human Services, says IHOT serves a broader population compared to Laura's Law.

He says the mental health professionals who make up three county IHOT teams work to get people in the program healthy and to find them resources including drug and alcohol rehabilitation. This year, 127 people are participating in San Diego County's IHOT program and nearly half of them are "engaged", meaning they've agreed to receive services.

But Dr. Michael Plopper, chief medical officer for Sharp HealthCare Behavioral Health Services, says while IHOT is a good program, it shouldn't be a substitute for Laura's Law.

"Laura's Law is the most reasonable way for people to get the treatment they need" he said.

Plopper says he sees emergency rooms full of people suffering from mental illness who come back time and time again and refuse treatment. He says implementing Laura's Law in San Diego would help reduce health care costs and over crowding in jails.